What does it mean to be an American?

We are finding, coaching and training public media’s next generation. This #nprnextgenradio project is created in Texas, where six talented reporters are participating in a week-long state-of-the-art training program.

In this project we are speaking to people representing a diversity of experiences and backgrounds in gender identity, physical ability, whether they are Indigenous, native born, a refugee or an immigrant without legal status—to ask what it means to be an “American.”

Maria Ramos Pacheco tells the story of Carlos Marentes. The 70-year-old has spent decades fighting for farmworker rights. “We’re supposed to protect every single person in this country, whether he was born here or not,” says Marentes.

Illustration by Ard Su

Meet the El Paso man fighting for farmworkers during COVID-19

Farmworkers have always been essential workers to Carlos Marentes — long before they were declared essential amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The 70-year-old has spent more than three decades advocating for their rights.

Marentes was born in Ciudad Juárez, México, and both of his parents were farmworkers. As a child, he dreamed of achieving the American dream: to have stable work and own his own home. Then, in 1970, he started to work in the fields of Albuquerque, N.M. He saw exploitation and abuses of human rights, and realized how vulnerable farmworkers were.

His first dream came to an end, but a life of fighting for farmworkers began.

El Paso man fights for farmworkers during COVID

Carlos Marentes is the director of the Centro de los Trabajadores Agricolas Fronterizos, located in El Paso, a couple miles from the U.S.-Mexico Paso del Norte bridge. (Photo by Maria Ramos Pacheco)

In 1977, he became a Texas Farm Workers Union volunteer and learned more about organizing and advocating for workers’ rights. A few years later, Marentes came back to El Paso and became the founder of The Border Agricultural Workers Project.

The project opened a center for farmworkers in 1994. Its goal: offer workers a safe place to stay near the port of entry between the U.S. and Mexico.

“Because it’s what America is: to protect the people,” says Marentes, who stresses the center is open to any farmworker, regardless of where they’re coming from or where they are heading — be it fields in New Mexico, California or New England.

“We’re supposed to protect every single person in this country, whether he was born here or not. But once you are here, you are American,” he adds.

It’s this dedication that has earned Marentes deep respect from farmworkers. They trust and listen to him.

Marentes speaks with Facundo García, who works at the front desk of The Borders Farmworkers Center to ensure every worker who arrives writes down their name and temperature. Jorge Zamago (wearing a hat) helps García with paperwork. (Photo by Maria Ramos Pacheco)

The center offers a space where workers can spend the night and sleep.

Farmworkers usually must be ready by midnight to get picked up by a contractor. From there, they’re taken to the fields. An average shift runs from around 4 to 5 a.m. until 3 p.m.

Once they are dropped off back outside the center, farmworkers can take a shower, eat, go to sleep and then repeat this routine.

During his years of activism, Marentes’s priorities have been fighting for safer conditions for farmworkers, along with living wages.

When the pandemic arrived in El Paso, priorities shifted: safety and survival.

Marentes joined the Texas Farm Workers Union in 1977 as a volunteer after experiencing the abuses and working conditions in the fields of New Mexico. (Photo by Maria Ramos Pacheco)

“I remember one worker asking me, ‘Entonces antes no eramos esenciales? So we were not essential before?’ They suddenly got that title,” Marentes says.

“But that title came empty. No better wages, better working conditions, in fact, not even the most basic measures of protection to deal with COVID-19 in the fields.”

Marentes explained the situation to farmworkers and urged them to take safety protocols to avoid getting infected. According to Marentes, that was almost impossible since workers are usually transported in packed cars, with no room for social distancing.

Despite these conditions, they kept working. After one farmworker was taken to the hospital, five others tested positive. Marentes knew he needed them to isolate. El Paso officials instructed him to take the workers to a hotel.

“So, I told them that they will have to ride on the back of my pickup, and they told me ‘OK, we are accustomed to always going in the back of a truck,’” he says.

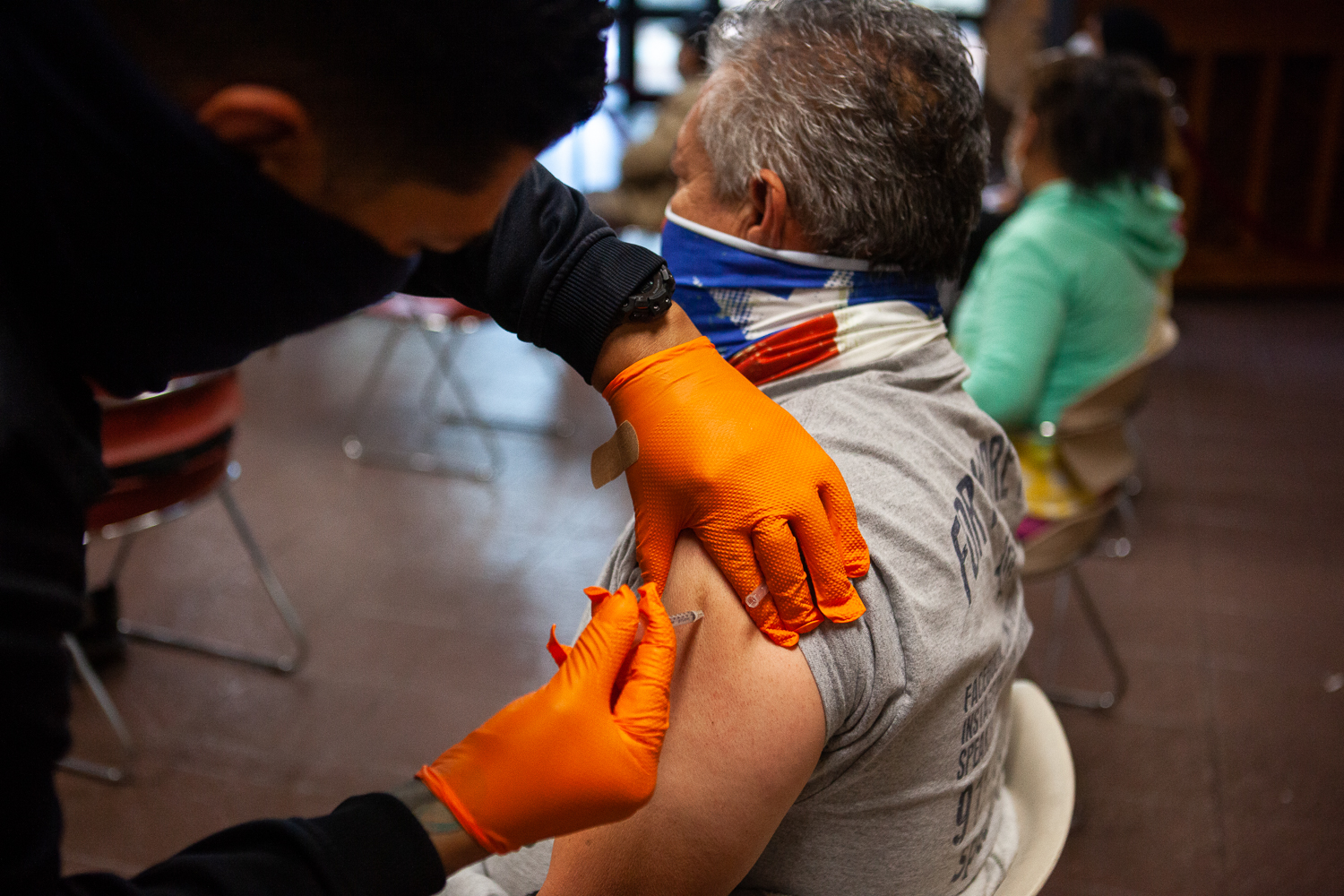

Marentes had to convince the city of El Paso to vaccinate farmworkers in April 2021 when the COVID-19 vaccine was not widely available. He also had to explain to workers what the vaccine was and why it was essential to get the shot. Here, Antonio Luevano, 54, gets vaccinated at an event Marentes organized for farmworkers and their families. (Photo courtesy of Corrie Boudreaux)

In the early days of the pandemic, Marentes recalls, farmworkers were most worried about their families.

“They told me, ‘Carlos y que van a comer nuestras familias?’ They asked me how are we going to feed their families if we’re going to be in isolation,” he says. They told him they needed to work.

Many of the farmworkers Marentes knew didn’t qualify for a stimulus check or government aid. That’s because about half of these workers in the United States — more than 1 million, according to the Department of Agriculture — are undocumented immigrants.

“You don’t imagine how hard it was for me to convince these workers to go in isolation. I have to promise them that every day I will send money to their families,” Marentes says.

Despite the challenges, Marentes has established a community. He continuously reminds farmworkers that what they do is vital to the country. They are part of America.

Marentes hopes to see the day farmworkers — as well as other service industry employees, like construction and cleaning workers — are not invisible to the eyes of society and finally receive the working and living conditions they deserve.